It is not uncommon to come across a patient brought into the emergency for syncope. Experienced clinicians are well aware that often despite extensive examination and investigations the cause cannot be confirmed. A recent paper has studied the prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients admitted for syncope (NEJM 2016; 375:1524-31).

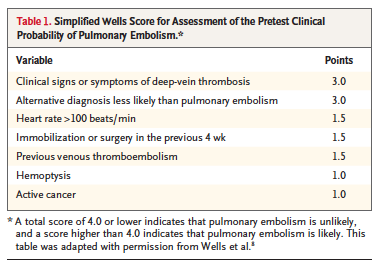

Researchers studied patients who were admitted for a first episode of syncope, in 11 Italian hospitals. A systematic work up for pulmonary embolism was conducted in all these patients of syncope. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) was ruled out in those patients who had a low pretest clinical probability, defined by the Wells score (<4), combined with a negative D-dimer assay. Computed tomographic (CT) pulmonary angiography or ventilation perfusion scanning was performed in all patients suspected of PE.

The potential explanations for syncope (in the 560 patients) were neutrally mediated (27%), orthostatic hypotension (20%), cardiac disorders (17%) and the cause was undetermined in 37% of patients.

Pulmonary embolism should be kept in mind when any patient with syncope is being assessed and more studies are needed to study the mechanisms involved in syncope with smaller pulmonary emboli.

Syncope is transient loss of consciousness that has rapid onset, brief duration, and spontaneous resolution caused by temporary cerebral hypoperfusion. Syncope can be neutrally mediated (vaso-vagal, carotid sinus syncope), can be caused by orthostatic hypotension 9drug induced, volume depletion, primary or secondary autonomic failure. Syncope is also due to cardiac arrhythmias, structural cardiac disease and due to often ignored pulmonary embolism. Most studies on syncope, too have not rigorously examined prevalence of PE in patients of syncope. Pulmonary embolism is therefore rarely considered as a possible cause of syncope despite being a treatable condition.

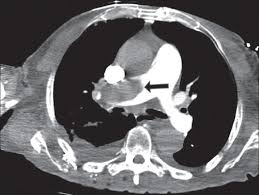

The Italian study included 560 patients (mean age, 76 years) in their study. Pulmonary embolism was ruled out in 330 of 560 patients (59%) by negative D-dimer assay and low pretest clinical probability. Pulmonary embolism was confirmed in 97 of the remaining 230 patients (42%). Hence prevalence of PE was 17% in the entire cohort. Evidence of an embolus in a main pulmonary artery or lobar artery or perfusion defects larger than 24% of the total area of both lungs was found in 61 patients.

This prospective study underscores the importance of keeping PE as a factor in all patients of syncope. It is well to remember that a high thrombotic burden was not always seen in PE with syncope; in fact 33% of patients who’s PE was confirmed by CT pulmonary angiography had no emboli proximal to segmental or sub segmental arteries. Pulmonary embolism was diagnosed in 25% of patients without any other explanation for syncope but also in 13% of patients with other potential explanation.

In 49 of the 73 patients (67%) of patients who had PE, the most proximal location of the embolus was a main pulmonary artery or a lobar artery. Of the 25 patients assessed by ventilation perfusion scan, 12 patients (50%) had a defect greater than 25% of the total lung area. These findings suggest that in half of patients with syncope due to PE there is an abrupt obstruction of blood flow by a large enough embolus, to result in sudden loss of consciousness.

However in 40% of patients, extent of pulmonary artery obstruction was smaller, suggesting additional factor such as a vasodepressor or cardio inhibitory mechanism for the syncope. It is also possible that a clot while traveling through the heart into the pulmonary artery may trigger arrhythmias resulting in syncope.