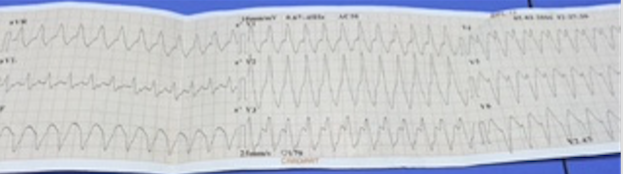

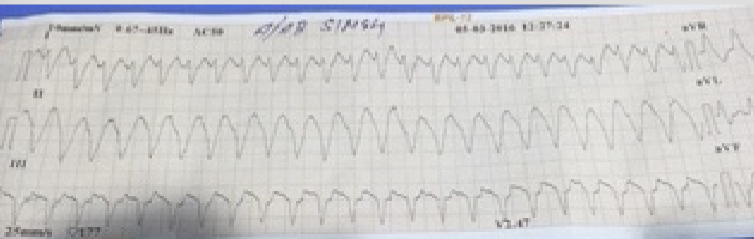

Recently an 85-year old man who had had CABG 2 decades ago was transferred from another hospital for self-terminating sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT). On arrival he had a heart rate of 80 per minute, blood pressure of 106/68 mm Hg, oxygen saturation of 95% on room air, his ECG showed sinus rhythm with old anterior myocardial infarction, and 2 D echocardiogram revealed severe septal/apical wall motion abnormality with an ejection fraction of 25%. The patient conceded that he had suffered a heart attack more than 25 years ago and was currently not on any specific treatment despite having symptoms of shortness of breath and tiredness.

I discovered on looking up the literature that older patients who survive an in-hospital cardiac arrest and subsequently get an ICD have a significantly reduced risk of death over the next 3 years. A study published (American Heart Journal) last year found that just 9 survivors of an in-hospital cardiac arrest would need to be treated for 3 years to save 1 life, but astonishingly less than one third of such patients receive an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator(ICD).

There are currently no clinical guidelines regarding ICD implantation for in-hospital survivors of cardiac arrest and therefore the researchers of this trial analyzed Medicare data from 2000 to 2008 to identify 1200 adult patients discharged after surviving a cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. The mortality rate over all was 44% , while of the survivors only 29% had got an ICD implanted. After propensity score matching (343 patients with ICD vs. 823 patients without an ICD) it was noted that the use of ICD was associated with a 24% lower mortality (adjusted hazard ratio 0.76; 95% CI 0.60-0.97). The lower mortality rate was almost to the tune of absolute 11%. The authors suggested based on this data that more survivors of cardiac arrest required ICD implantation; there is a potentially modifiable process of care, which could improve long-term survival in this high-risk population.

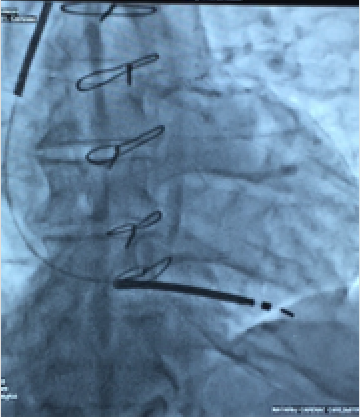

Our patient was slightly different in the sense that he did not suffer pulseless VT but he was a candidate for an ICD and when explained the situation readily consented. There was no electrolyte disturbance , no evidence of acute ischemic event, and no drug abuse. The patient consented to implantation of a single lead ICD, which was successfully done and the patient discharged after 2 days on a beta -blocker, an ACE inhibitor, eplerenone, aspirin, clopidogrel and a statin.

No defibrillation threshold (DFT) testing was attempted during impaction of the ICD. Till recently most patients receiving an ICD underwent DFT testing, but it has been realized the over whelming majority of such patients do not benefit from DFT testing. The Shockless Implant Evaluation (SIMPLE), randomized 2500 patients to DFT testing versus no testing during ICD implantation. There was no benefit observed in the DFT group; patients assigned to the no DFT arm did not have significant failure of arrhythmic shocks or death. The researchers concluded based on their data that implanting an ICD without routine testing should be the preferred approach. The SIMPLE trial conducted in 18 countries studied ICD implanted for primary or secondary prevention; with 1253 patients in the perioperative DFT testing arm and 1247 patients in the no DFT cohort. The testing protocol required 1 successful termination of ventricular fibrillation with a 17 J shock or 2 successful terminations at 21 J. Follow up averaged 3.1 years. Routine DFT testing is no ,anger done in Canada.

The annual rate of primary end point (failed appropriate shock or arrhythmic death ) was 7.2% in the no testing group and 8.3% in the DFT tested group, for a hazard ratio of 0.86 (p < 0.001 for non-inferiority). Moreover there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality. There was no significant difference in sub groups like of very low LVEF, those with biventricular pacemakers, atrial fibrillation or advanced heart failure patients. The latest generation ICD’s because of their efficiency make it easier to do without DFT.

Astonishingly less than 10% patients needing ICD as primary prevention actually get the device. This is American data. The current issue of JACC has published the US National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry that reveals only 61% of patients received beta-blocker and renin-angicensin inhibitor (RAI) before ICD implantation and worse only 28% were administered an adequate supply (defined as 80% coverage for the 90 days before ICD implantation. Obviously there are huge gaps in medical therapy following myocardial infarction or in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). It is therefore imperative that optimal heart failure therapy is provided to patients who are potential candidates for an ICD.

The Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial of patients with New York Heart Association functional class II and III and LVEF <35% reported that approximately 96% patients were on RAI and 69% were on a beta blocker.

In the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II, approximately 70% of patients with history of a myocardial infarction and LVEF <30% were on a RAI and beta blocker.

The situation is ,however, quite different in the real world from randomised trials. Patients of HFrEF have to be identified for optimal heart failure treatment in order to arrest and reverse myocardial dysfunction , improve quality of life and above all reduce the need for a device such as an ICD or a biventricular pacemaker.It should be noted that optimal medical therapy in non-ischemic HFeEF substantially improves LVEF over the next 3-6 months. A rise in LVEF by 10% has been observed in almost 70% of patients given RAI and a beta-blocker ; and 20% increase in LVEF has been recorded in 39% of optimally treated patients (Intervention in Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy-2 study). Most cardiac societies therefore insist on a waiting period of 3-6 months in patients with non-ischemic HFrEF before implantation of an ICD.