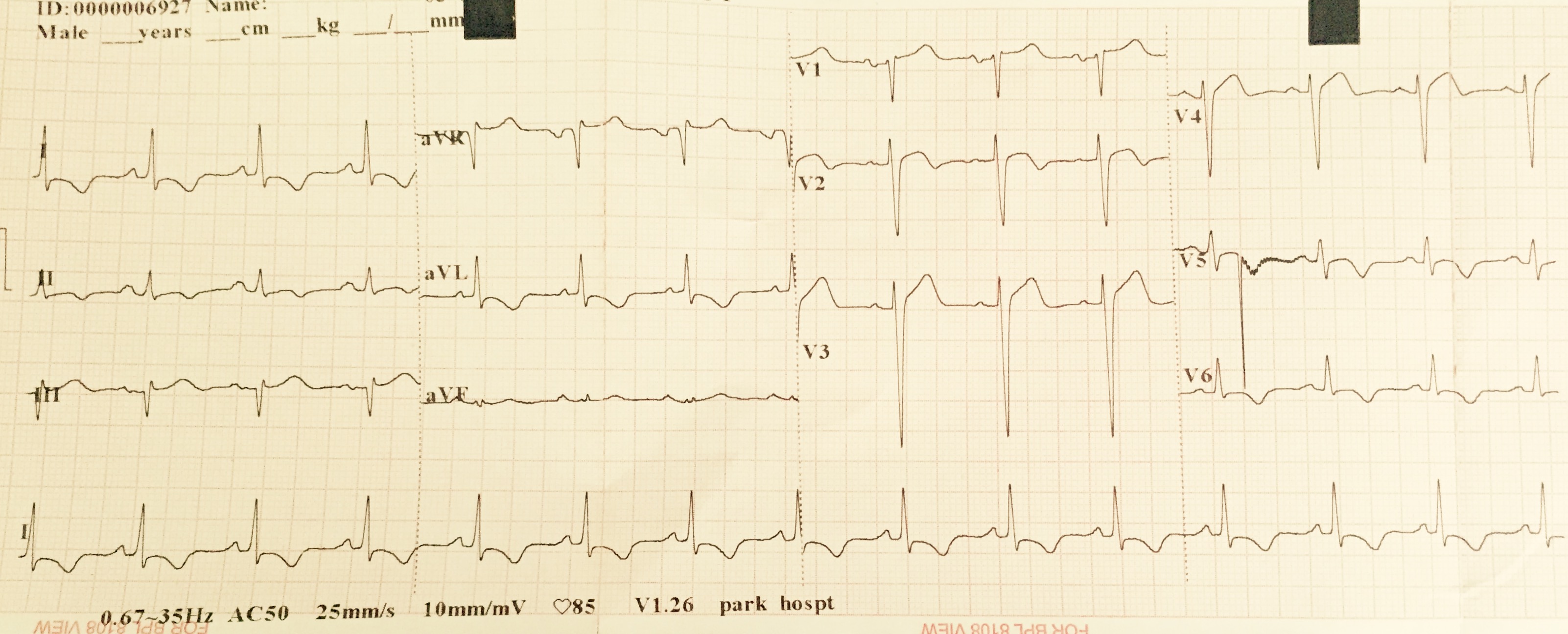

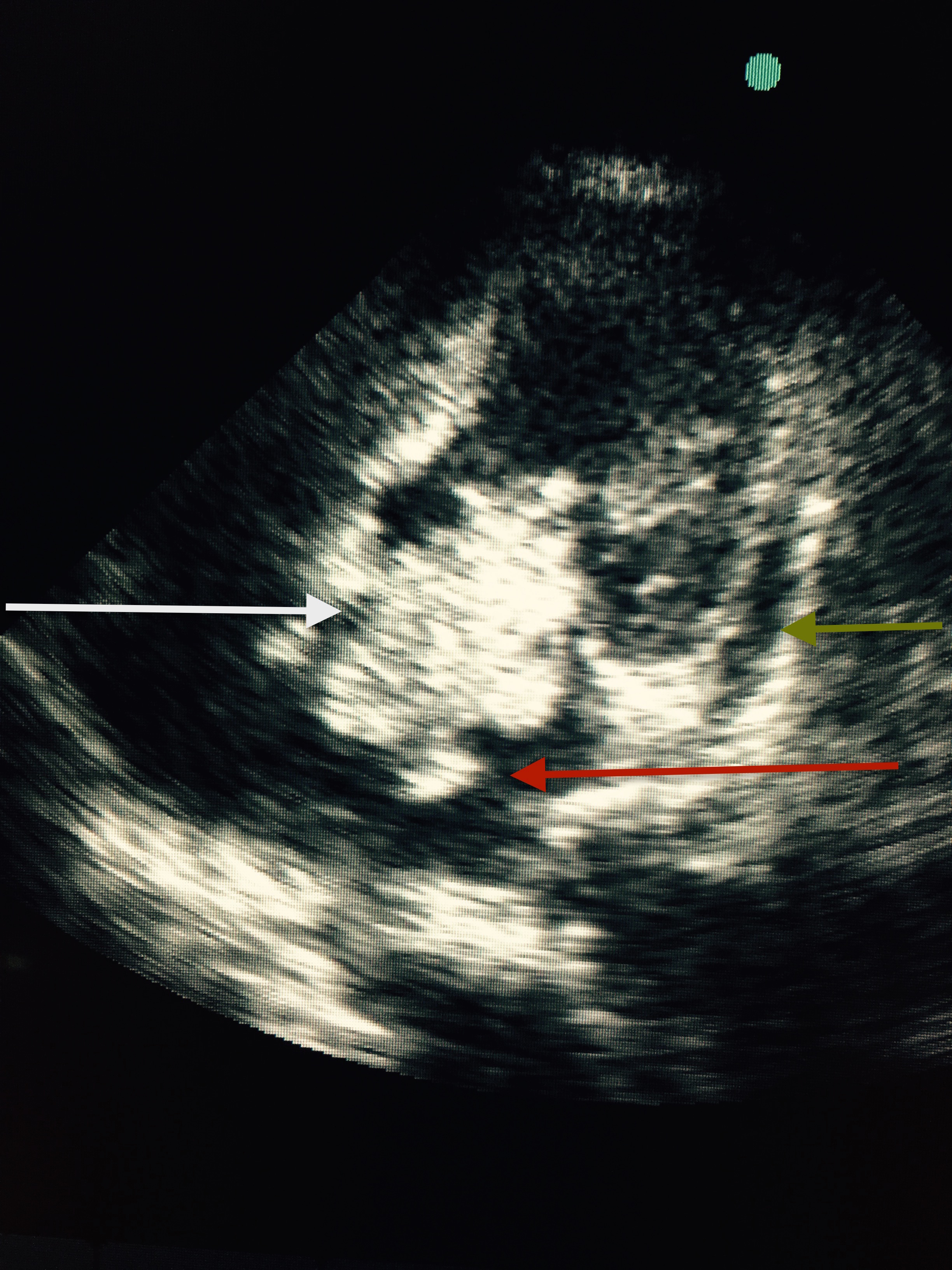

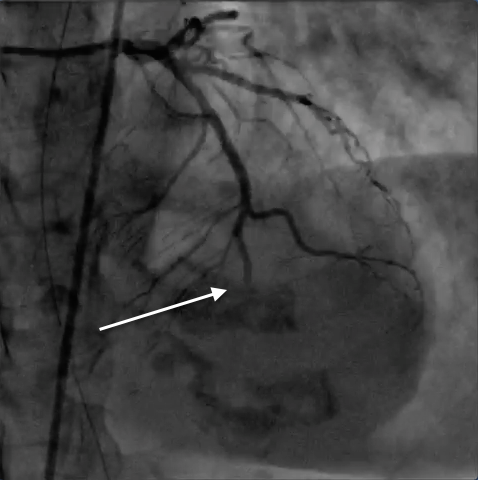

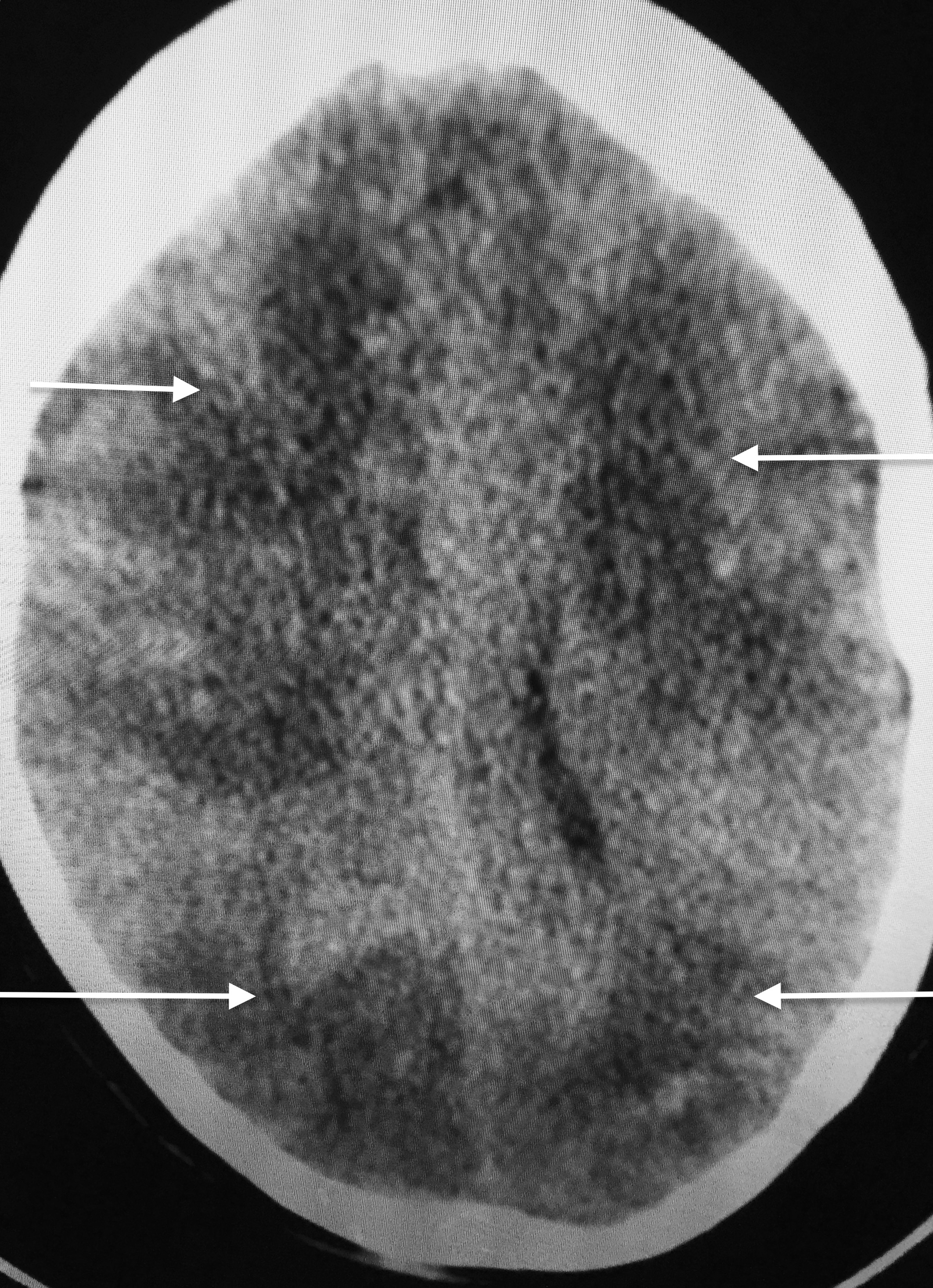

A 60-year old woman entered the emergency with complaints of chest discomfort accompanied by breathlessness for the previous 3 hours. The patient had previous history of diabetes and hypertension but no episodes of joint pains, fever, or weakness of any part of her body. She did admit to tiredness and easy fatigability for 3-4 months before admission. Her physical examination revealed a raised respiratory rate of 28 per minute, blood pressure of 104/60 mm Hg, and temperature of 37.6 C. She had, on auscultation, normal heart sounds with a diastolic murmur. There was no evidence of heart failure in the form of crepitation in the lungs. Her 12 lead Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm with inverted T waves in leads L1, AVL, and V5-V6 (Figure 1). Transthoracic 2 D echocardiogram (2 chamber view) showed apico-septal hypokinesia, left ventricle ejection fraction of 54%, and a large globular mass 5 X 3.7 cms in the left atrium (LA). The tumor (white arrow) was attached to the interatrial septum (fossa ovalis area ) and would prolapse through the mitral annulus into the left ventricular cavity in each cycle of diastole. The mass was quite mobile with a satellite breakaway piece observed at 6 o’clock position (red arrow); there was mild pericardial effusion (Figure 3; blue arrow). The patient was shifted to the cath-lab where her coronary angiography demonstrated near total occlusion of her mid distal left anterior descending artery (Figure 3;white arrow) Before any intervention could be attempted the patient had a small fit and rapidly lost consciousness. She was transferred to the intensive care unit in a hemodynamically stable condition but she was no longer responding to any verbal command and she had no voluntary motor movement. There was no response to painful stimuli and she had bilateral extensor responses. Urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed multiple massive bilateral infarctions in both cerebral hemispheres (Figure 4; white arrows). The patient progressed to unresponsive coma requiring temporary mechanical ventilation; she subsequently regained spontaneous respiration underwent tracheostomy. The cardiac enzymes were raised significantly (creatine kinase 940 U per litre, a creatine kinase MB isoenzyme level of 124 U and troponin T level of 3 ng per milliliter); while her full blood count and biochemistry were within normal limits. She did not have anti-nuclear antibodies .The patient did not have splinter hemorrhages,Osler’s nodes or Janeway’s lesions.

The next of kin (her son) did not consent to surgical removal of the tumor in view of the severe comprehensive neurological deficit.

Eighty percent of primary tumors in the heart are benign and myxomas account for more than 50% of these. Metastatic tumors involve the heart, pericardium or both from some other organ and are 40 times more common than primary tumors; they originate from the lung, breast, lymphomas, thyroid, esophagus and the kidney. The secondary tumors are more frequently carcinomas than sarcomas. Pericardial metastases are the most common (69%), followed by epicardial (34%), myocardial (32%) and endocardial metastases. Secondaries to the heart are multiple. Rhabdomyoma is the most common tumor seen in children (40-60%), while malignant primary tumor are sarcomas (1-2). The only tumors not known to metastasize to the heart are tumors of the central nervous system.

Intracardiac myxoma is the most frequent benign tumor with 75% located in the LA, followed by the right atrium (18%), right ventricle (4%) and left ventricle (4%). Myxomas have been reported to originate from the mitral annulus, mitral valve, aortic valve, pulmonic valve and the inferior vena cava; it is however widely considered that true myxoma arises from the mural endocardium (3-5). Myxomas arise most commonly in patients in their 30’s to 60’s, albeit myxomas have been seen in infants, children and elderly. Children have a higher incidence of myxomas in the ventricle; most series have reported a higher incidence in females.

Myxomas largely occur sporadically but may be familial, and uncommonly have been described as part of the Carney complex, which occurs at a younger age. The Carney complex is an autosomal dominant condition in which cardiac myxomas are accompanied by mammary or cutaneous myxomas, hyper-pigmented skin lesions, and hyperactive pituitary, adrenal or testicular gland. The other benign tumors of the heart have been noted as fibromas, lipomas, hemangiomas, and paragangliomas. Extraadrenal pheochromoctyomas and paraganglionomas are frequently accompanied by palpitaipons, flushing and tachycardia (6).

Most patients present with features of constitutional, obstructive or embolic symptoms (7). Cardiologists usually come across patients with myxoma presenting with palpitations, exertional breathlessness, or syncope. Constitutional symptoms consisting of fever, weight loss, fatigue, anemia (often hemolytic) are present not uncommonly in patients with a myxoma, probably by over production of interleukin-6. Systemic embolization may occur in 40% to 50% patients with LA myxomas especially in the presence of irregular and frond like surfaces. Tumor surfaces or surface slots can embolize to the cerebral arteries (as in this case), kidneys, extremities, and to the coronary arteries (as in this case). A complete myxoma has been known to detach and lodge in the aortic bifurcation (8-9).

Embolization to the brain occurs in about 50% of embolic events with LA myxomas. This may be the first systemic manifestation, is more common in the left cerebral hemisphere and may be multiple or massive. The onset of neurologic deficit may be gradual or sudden. Cardiac myxoma is however an infrequent cause of ischemic stroke; occurring in 0.5% of acute stroke patients, with women in the fifth decade at greatest risk (10-11). The first case report describing multiple large embolic infarcts to the brain was reported by the Mayo Clinic; the patient a 63-year old woman, rapidly deteriorated into deep coma and died; tragically the myxoma had been missed earlier on clinical and echocardiographic examination. Post mortem revealed a large LA myxoma with tumor emboli to multiple organs, and a shower of myxomatous material occluding both carotid arteries and branches of both the anterior and posterior cerebral circulation.

Myocardial infarction as the first manifestation may present with LA myxomas because of embolization into a coronary artery (12-13). This case, to the best of our knowledge, is the first report of a middle aged woman presenting with an acute STEMI (confirmed by coronary angiography) accompanied simultaneously by massive multiple cerebral embolization leading to deep unresponsive coma.

Trans thoracic two-dimensional and trans-esophageal echocardiography are well-documented techniques for demonstration of cardiac tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging achieves good visualization of the size, shape and mobility of intra-cavitary atrial myxomas. Tumors unlike thrombi in the heart are enhanced with gadolinium injection during MRI. (14-15). The only definitive treatment of cardiac myxoma is surgical removal. Life long follow-up is required because there may be recurrence in 1-5% in sporadic cases and up to 20% in the familial variety (16).

The first case to be operated in the US was a 33 years male who suffering from breathlessness and hemoptysis, was found to have a loud second pulmonic sound, a diastolic murmur and an “opening snap”. He was diagnosed as severe mitral stenosis and set up for mitral valvotomy using the postero-lateral approach. The surgical team had to beat a hasty retreat when they discovered a soft lemon-sized mass attached by a narrow pedicle to the base of the interatrial septum. The mitral valve was anatomically normal (there was no echocardiography available then). The patient had a second surgery 3 weeks later when under hypothermia but without cardio-pulmonary bypass, the tumor was removed successfully after numerous episodes of ventricular fibrillation during surgery necessitating defibrillation (17).

Our patient continues to be hospitalized in the intensive care unit in deep coma with tracheostomy, no motor activity, and some eye movements. The direct next of kin are mulling over surgical removal of the tumor because of her severe neurological deficit; they are yet to give consent for surgery albeit the patient is hemodynamically stable. This is a rare patient of a left atrial tumor presenting simultaneously with acute anterior myocardial infarction and multiple massive bilateral cerebral emboli. The histopathology of the tumor remains to be ascertained but statistics weigh in favor of the tumor being a myxoma.

REFERENCES.

- McManus B. Primary tumors of the heart. Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 10th ed; 2015:1863-75.

- Burke A P, Virmani R. Pediatric heart tumors. Cardiovasc Pathol 2008; 17: 193.

- McAllister H, Hall R, Cooley D. Tumors of the heart and pericardium Curr Probl Cardiol 1999; 24: 57-116.

- Lam KY, Dickens P, Chan AC. Tumors of the heart: a 20-year experience with review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993; 117: 1027-31.

- Burke AP, Cowan D, Virmani R. Primary sarcomas of the heart. Cancer 1992: 69: 387-95.

- Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes G J. Malignant tumors of the heart. A review of tumor type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol (R coll Radiol) 2007: 19:748.

- Peters MN, Hall RJ,Colley DA, et al. The clinical syndrome of atrial myxoma. JAMA 1974; 230: 695-701.

- Misago N, Tanaka T, Hoshii T, et al. Erythematous papules in a patient with cardiac myxoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol 1995; 22: 600-605.

- McMullin G M, Lane R. A rare cause of acute aortic occlusion. Aust N Z J Surg 1993; 63: 65-68.

- Brown WT, Wijdicks EF, Parisi J E, et al. Fulminant brain necrosis from atrial myxoma showers. Stroke 1993; 24: 1090-1102.

- Knepper L E, Biller J, Adams HP Jr, Bruno A. Neurologic manifestations of atrial myxoma: a 12 year experience and review. Stroke 1988; 19:1435-1440.

- McAllister HA Jr. Primary tumors and cysts of the heart and pericardium. Curr Probl Cardiol 1979: 4: 1-51.

- Cheitlin Md, McAllister HA, de Castro CM. Myocardial infarction without atherosclerosis. JAMA 1975; 231:951-959.

- Kamata J, Yoshioka K, Nasu M, et al. Myxoma of the mitral valve detected by echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 1995;16:1435-1438.

- Leibowitz G, Keller N M, Daniel W G, et al. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography in the evaluation of right atrial tumors. Am Heart J 1995; 130:1224-7.

- Putnam J B Jr, Sweeney MS, Colon R, et al. Primary cardiac sarcomas. Ann Thoracic Surg 1991; 51:906-910.

- Ekmektzoglou K A, Samelis GF, Xanthos T.Heart and tumors. Location, metastasis, clinical manifestations, diagnostic approaches and therapeutic considerations. J cardiovasc Med 2008; 9:769.

- Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial myxoma. A series of 122 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001; 80:159.

- Scanell JG, Brewster WR, Bland EF. Successful removal of a myxoma from the left atrium. N Engl J Med 1956; 254:601-604.