Sir James Black significantly contributed to the history of medicine by discovering not one but 2 great medicines. The second one was cimetidine a reasonably powerful anti peptic ulcer drug that he figured out would be effective based on the fact that histamine a powerful stimulant of gastric acid secretion was used as a diagnostic test to detect the susceptibility of a person to develop a peptic ulcer.

But probably more revolutionary was the development of propranolol in the 1960s by Black who studied medicine in Oxford. Black realized way back in the 1950’s that one way of tackling narrow arteries was to reduce heart rate and force of contraction of the human heart. In other words lower the need of oxygen. This led to his discovery of propranolol. Black won the Nobel prize in 1988 for “discoveries of important principles for drug treatment”.

Black was a pioneer in understanding the role of cell “receptors” and how they could be modified to alter or prevent harmful effects. He suggested that a synthetic compound similar to adrenalin could act as a false key, attaching to so called beta-receptor sites to prevent adrenalin from entering the cell. Propranolol, the first of the new class beta-blockers were discovered in 1964, 2 years after the Indo-Chinese war. Propranolol became to be widely used in treating angina, blood pressure, heart attack and migraine. The discovery of propranolol was considered the biggest breakthrough in the treatment of heart disease since digitalis was discovered in the eighteenth century. It soon became the world’s best selling drug.

In the 1980’s the BHAT (Beta Blocker Heart Attack) trial and the Norwegian multicenter study showed a survival benefit with a beta-blocker after a non-perfused acute myocardial infarction. However with the advent of reperfusion therapy (thrombolytic agents and then PTCA with stenting) further brought down reduction mortality from 25% to only 5%. Percutaneous coronary intervention not only reduced infarction size but also thereby lessened the chances of arrhythmia or heart failure (HF). Moreover there has been tremendous advancement in drug therapy since the 1960’s and 1970’s. We have now available with us apart from beta-blockers, drugs such as ACE inhibitors, ARB’s, statins, and of course good old aspirin accompanied by other more powerful antiplatelet medicines such as clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor.

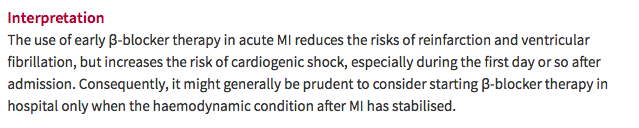

Admittedly although the discovery of beta-blockers was revolutionary in heart disease management 5 decades, other equally or more effective drugs have been tested in large randomized trials involving thousands of patients. Beta-blockers even today are standard treatment for all patients of acute myocardial infarction, both ST-elevation (STEMI) and non-ST elevation (NSTEMI) myocardial infarction. But the role of beta-blockers remains undisputed in patients with heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction in patients with ischemic or non-ischemic heart failure. But most published trials on beta-blockers after STEMI were done decades ago, when reperfusion therapy was not used nor were statins available. In the large COMMIT trial no patient had PTCA or stenting, and 45% of patients did not receive thrombolytic therapy. Most patients with MI including those with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction were prescribed a beta-blocker. The COMMIT trial using intravenous metoprolol followed by oral metoprolol demonstrated reduction in recurrent MI at 28 days but no reduction in deaths.

The role of beta-blockers in patients with preserved ejection fraction post MI remains unclear and even controversial. A French registry that included 2679 consecutive MI, found that early use of beta-blocker is associated with substantial reduction in risk of 30-day mortality in patients with acute MI without heart failure. At one year there was no significant difference in mortality. Discontinuation of beta-blocker at the end of one year was not associated with increased 5-year mortality. The French registry included only acute MI patients without heart failure or left ventricle dysfunction (BMJ 2016; 354:i4801)

The European guidelines have downgraded the level of recommendation from class I to class IIa because of lack of evidence of the usefulness of beta blockers, whereas American guidelines still give the highest level of recommendation for beta blockers both in STEMI and NSTEMI patients; class I recommendation.

A large observational study (median follow-up of 44 months) including more than 44,000 patients with either CAD risk factors only, known previous MI, or known clinical CAD without MI, also failed to show any association with lowering of composite cardiovascular events. Of the 44,708 patients, 21,860 patients were included in the propensity-matched analysis. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke (JAMA 2012; 308:1340-1349).

This weeks JACC carries a prospective observational cohort study that reports no reduction in the risk of mortality at 1 year among patients with acute MI without heart failure or LV systolic dysfunction. The lack of association with survival with a beta-blocker was evident at 1 month, 6 months and 1 year. Of 92,000 patients with STEMI and 90,000 patients with NSTEMI, 96% to 93% patients received beta-blockers. There was no significant difference in deaths after adjustment between those patients who got a beta-blocker and those who did not. A total of 179,000 surviv0rs of hospitalization with acute MI without heart failure or left ventricle systolic dysfunction were assessed between 2007 and 2013, hence almost all patients were getting contemporary treatment. The study reveals that in the absence of heart failure or left ventricle systolic dysfunction the use of beta-blockers provides no clinical advantage over those patients who do not.

The lack of efficacy was found both in patients of STEMI and NSTEMI. Beta-blockers are known to produce uncomfortable side effects and also adding them to a secondary prevention prescription could result in poor compliance. A meta-analysis of 31 studies reported about 25% reduction in risk of death with the use of beta-blockers, but most of these studies were conducted before PTCA and stenting. A meta-analysis of 10 observational studies including 40,000 suggested little benefit with routine use of beta-blockers in all patients with acute MI who received PCI. Beta-blockers were effective in patients with reduced LV ejection fraction, NSTEMI, or in patients given inadequate secondary prevention (Am J Cardiol 2015; 115:1529).

Therefore the take home message would be that albeit beta-blockers are very effective in patients with heart failure or left ventricle systolic dysfunction, they may provide no additional advantage in patients of acute MI without a compromised left ventricle in the current era of primary PTCA accompanied with stenting.