Recently my 94 years old Dad who suffers from hypertension ischemic cardiomyopathy (left ventricle ejection fraction of 22 %) Addison’s disease an enlarged prostate and internal hemorrhoids complained of sudden onset palpitations when I returned from hospital in the evening. The palpitations had been on for the last 2 hours and made him both weak and breathless. I realized his heart rate was quite fast and for a moment my heart was in my mouth as I anticipated ventricular tachycardia; but very soon I realized the pulse was irregularly irregular and moreover reasonably well felt. He was in atrial fibrillation (AF). I told him to hang in while I got in reinforcements. I actually drove to Prayag Hospital (5 minutes away from home) and borrowed a cardiac monitor that they gave me without a moment’s hesitation. I also quickly bought 3 ampules of injection amiodarone; a vac of 5% dextrose for dilution and a 20 cc syringe.

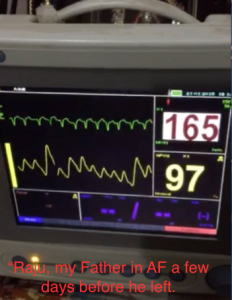

I hooked Dad to the cardiac monitor to confirm that it was a narrowish QRS tachycardia and definitely AF. The heart rate was in the 170’s. No wonder he was in discomfort. I gave him one ampule (150 mg) of amiodarone slowly intravenously but the AF carried on. I tried another 2 ampules of amiodarone diluted in 5% dextrose, but the AF persisted. The heart rate did fell to the nineties. I found the situation a bit disconcerting because, in my experience, recent onset AF usually responded to a couple of ampules of amiodarone. The potential of an embolic stroke weighed heavily on my mind and I rushed out to get an injection of 2.5 mg subcutaneous fondaparinux (an indirect factor X antagonist), which I injected, in his abdomen. This would serve as a necessary anti-coagulant for some time. The AF persisted and went on till the next day; Dad stayed hooked on to the monitor; and I by now had become deeply concerned if not also a bit despondent. Dad did not wish to be admitted into an intensive care. To make matters worse his hemorrhoids bled the next day after many months (fondaparinux effect). I had a major problem; a 94 years old Dad with severe left ventricle systolic and diastolic dysfunction on the brink of acute heart failure because of the fast and erratic heart rate; also the threat of a looming embolic stroke. I gave him yet another injection of amidarone (the fourth ampule) and this time mercifully soon after the full injection, Dad reverted to sinus rhythm. I could feel my muscles relaxing and I gave out a huge sigh of relief. Dad too felt immediately better, stronger and more self-confident. I promptly put him on an oral regimen of tablet amiodarone of 200 mg twice a day for a week and then maintenance of 200 mg a day. I decided against oral anticoagulation (OAC) in view of his hemorrhoids and a hemoglobin level of 10 gm.% (he has always been a strict vegetarian); and particularly because he had achieved sinus rhythm. There was always the danger of his falling; more so because he was almost blind in both eyes due to glaucoma and retinal degeneration.

Importantly as these events were unfolding an excellent paper was published in the Journal of American College of Cardiology (JACC 2015; 65:225-32) that concluded a patient with AF had a true stroke rate of only 0.7% per year if the CHA2DS2-Vasc score was 1;after examining retrospective data in more than 140,000 patients; and thus there was little advantage on prescribing OAC to such patients. Both the American and European guidelines on AF emphasize the utility of the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system in assessing risk of stroke in AF. The Europeans have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 as threshold to begin treatment whereas the Americans had kept a higher threshold of 2.

The CHA2DS2-VASc score is an acronym (1 point for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, but 2 for age >75 years and a previous stroke or TIA. Patients aged more than 65 years and female patients are also at greater risk of stroke. The Swedish cohort used in the 2012 European guidelines had a hazard ratio of 2.97; while hazard ratios for the remaining 1-point risk factors ranged from 0.98 to 1.19. This means a patient between 65 to 74 years may be at high enough risk to merit OAC treatment but patients with only one of the other risk factors may be below the 1% threshold. The European Society of Cardiology recommends treatment either with warfarin (a vitamin K antagonist) or preferably one of the new OAC agents (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban).

The study published in JACC recommends that the risk of stroke seems lower than previously considered in patients with CHADS-VASc score of 1, and therefore OAC in such patients could be harmful and unnecessary. It also points out that previous studies have included pulmonary embolism and transient ischemic attacks (TIA) in their data and thus substantially exaggerating the incidence of ‘stroke ‘ in patients with AF and score of 1. There was an inflation of almost 44% in incidence of ‘stroke’ when pulmonary embolism and TIA were included. It had been earlier calculated that the tipping point when benefit outweighed risk was a stroke risk of 1.7% with warfarin; and 0.9% with the newer OAC’s. The Americans have kept the threshold at 2 or more to start anti-coagulation in AF. The Europeans may have to revise their threshold with the publication of the JACC paper.

To summarize it would be prudent to initiate anti-coagulation with warfarin or OAC’s when the CHA2DS2-VASc score is 2 or more. My DAD has a score of 4! But given the fact that he is now in sinus rhythm and the presence other co- morbidity, I would rather not start him on oral anti-coagulation. Moreover there is no randomized data on treatment of cardiovascular disease in people in the nineties.

It would be worthwhile mentioning that a recent meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials involving more than a 100,000 patients of either AF or venous thromboembolism, reported that the new OAC’s as compared to vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) significantly reduced risk of overall major bleeds (relative risk [RR] 0.72, P<0.01), fatal bleeding (RR 0.53, P <0.01), intracranial bleeding (RR 0.43,P<0.01) and total bleeding (RR 0.76, P<0.01). There was also no significant difference in major gastrointestinal bleeding between the OAC’s and warfarin (Blood 2014; 124 (15): 2450-2458).

The NICE guidelines state that stroke prevention treatment is not to be offered to people with AF but below 65 years and no risk factor. Treatment with OAC’s when recommended should always be weighed with risk of bleeding in every patient, keeping in mind that anticoagulation is underused in the management of AF. Albeit anticoagulation has been shown to reduce strokes by 50% in older people as compared to aspirin, the latter is often preferred for treatment.